Becoming Saints in the Last Days

A life in formation

I was born in Provo, Utah to two Brigham Young University students in April 1984. A few weeks after I was born, my parents dressed me in white and presented me in front of their congregation (we call them wards) of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. My father held me and made a prayer circle with 7 or 8 other men in the congregation and gave me a name and a blessing for my life. He blessed me with health, love, and faith.

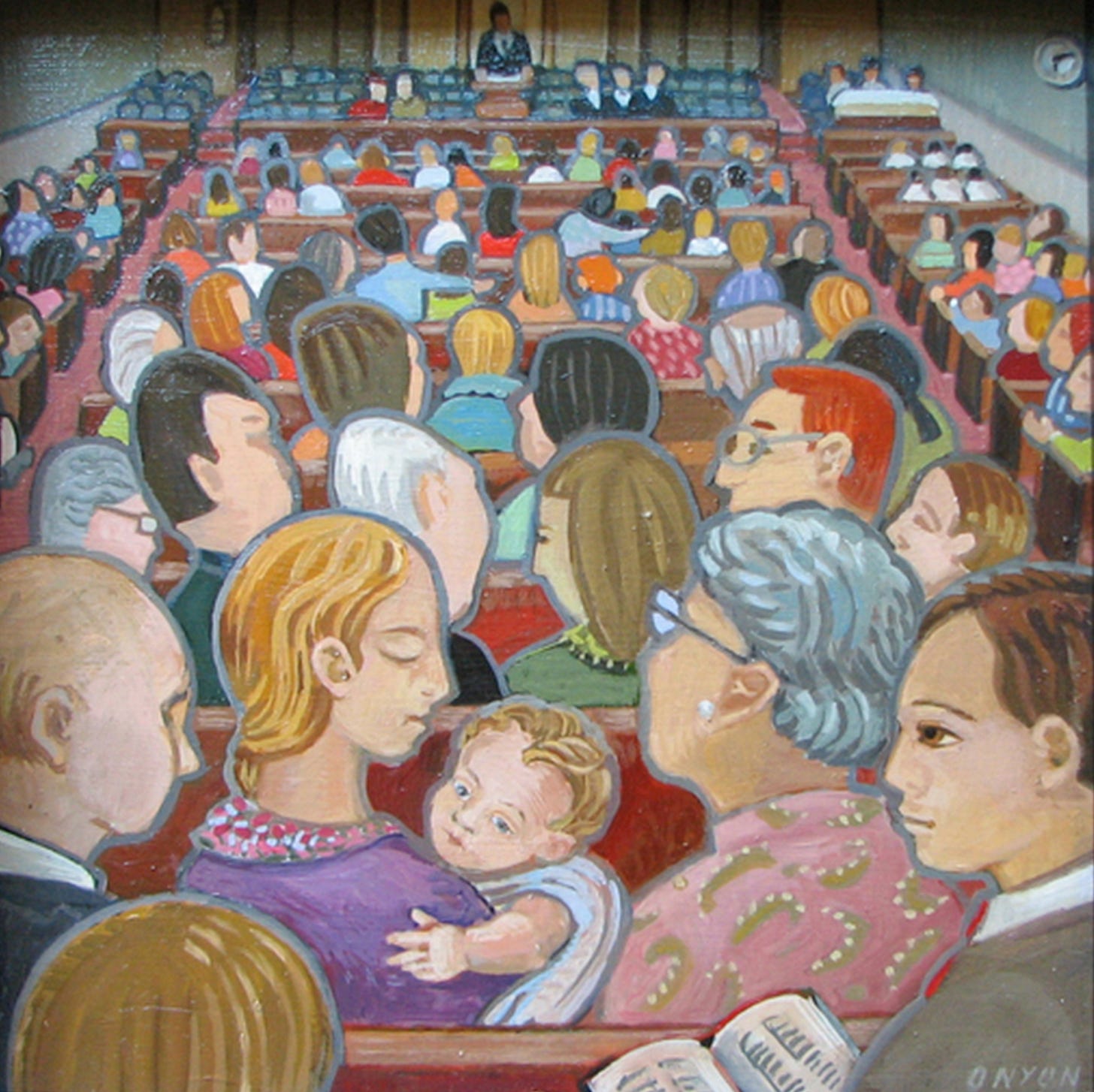

Every Sunday without fail my parents brought me to church with them. The first hour was sacrament meeting, where the bread and water was blessed and passed, and members of the congregation give short sermons. The second and third hours were for instruction, the Sunday school portions. When I was 2, I began going to nursery, a daycare during church where a few adults watch the children and teach them basic lessons. This allowed my parents to attend the classes.

Those nursery workers were not paid for watching the kids. It was a volunteer position. They were assigned that role (called a calling) by the ward leader, called a Bishop, who is also a volunteer. He could be a dentist or an accountant or a teacher. The bishop typically serves for 5 years. The sunday school teachers were also volunteers. Every person in the ward was expected to serve and given callings—jobs include: youth teacher, greeter, charity coordinator, scout troop leader, bookkeeper, janitor, post-church snack provider.

Not only is every ward member expected to donate their time to serve, they are also asked to contribute 10% of their income towards tithing, to support the mission of the church.

When I turned 5, I began attending primary, which are age appropriate church classes for kids—we sang songs like “I am a child of God” and “I’m trying to be like Jesus.” We read scripture verses and discussed their meaning. We learned about Joseph Smith and the subsequent prophets of the church.

When I was 8, I put on a white outfit and was baptized in a font full of water by my father. My extended family and the whole ward was in attendance. I was then confirmed and given the gift of the Holy Ghost to be my constant companion. My parents gave me a leather bound set of LDS scriptures with my name engraved in gold letters. It had four books—the Bible, the Book of Mormon, the Doctrine and Covenants and the Pearl of Great Price. The pages were impossibly thin. I gently marked my favorite passages with a delicate red-colored pencil.

When I was 12, my father laid his hands on my head and ordained me to the Aaronic priesthood and the office of deacon. I was now authorized to pass the sacrament—the bread and water—to members of the ward. Every Sunday, after the blessing on the sacrament, I was given a tray of bread and walked up and down the pews to deliver the Lord’s supper. I was expected to keep myself morally clean in order to be worthy of this responsibility. I was encouraged to prayer on my knees every morning and every night and to search and study the scriptures.

At age 13 we moved to St. George, Utah, a relatively small desert town in the southwest corner of Utah near Zion national park. The city was surrounded by rust-colored bluffs. We joined our new ward and my parents were given callings. I began to accompany my father on home teaching visits, where were assigned a family in our ward to care for, both spiritually and materially. We would show up once a month, share a gospel message, and find out if they had any needs.

I was now old enough to enter our local temple—a massive, gleaming white building in the exact center of town. I performed proxy baptisms for my ancestors and other people’s ancestors, helping to extend Christian salvation to all of humanity and linking all human beings together in an eternal family.

At 15 I began attending seminary, a daily religious instruction class before high school. We memorized scriptures, and learned theology and history.

At 16 I was ordained to the office of priest, which enabled me to say the blessing over the bread during Sunday services.

Once a month, the ward fasted for 24 hours and donated the money they would have spent to support families in need. I would go door to door to collect those donations and give them to the bishop. My neighborhood was 90% Mormon, pretty much every person in my area knew my family, knew my name and encouraged me in my spiritual growth.

At 17, I was taken to the basement of a man named Clayton Farnsworth, who was our stake patriarch. He gave me a patriarchal blessing, telling me my spiritual lineage in the house of Israel and prophesying about my life.

At 18 I was ordained to the Melchezidek priesthood and received the sacraments of washing and anointing. I was given a new sacred name. I made covenants to live the gospel of christ, be obedient, live a chaste life, and consecrate all that I have to the kingdom of God. I began wearing special undergarments that remind wearers of these covenants.

At 19 I began a 2 year mission in Spain. Every day, I woke up at 6am, read scriptures and prayed, and taught strangers and church members lessons about Christ and core teachings of the LDS church—that the fullness of Christ’s church had been lost since the apostles, that the prophet Joseph Smith was chosen by God to restore Christ’s Church, that the Book of Mormon was a true book of scripture, that faith, repentance and baptism were the path of life and true joy. I lived a life of obedience, poverty, humility and service.

I didn’t teach some of our other, more radical doctrines to the public, but I privately marveled at them—that mortality is a school for becoming Gods, that the universe was infinite and full of a divine community I belonged to, that we have a heavenly mother, that I was born with a sacred purpose to gather God’s children on this earth into one great whole under Christ.

I returned home from my mission and enrolled at Brigham Young University, the same church-owned school my parents went to. Our school’s mission was enter to learn, go forth to serve. I studied in order to be of service to my future family, my community and the world. Alcohol, drugs and sex was not allowed. I made beautiful friendships with young idealists and we discussed philosophy, culture and theology into the night.

When I was 26, I moved to Washington DC and went to a retreat in Outer Banks, North Carolina for young Latter-day Saints on the east coast. I was bored by the beach volleyball and retreated to the house to read. I noticed a young woman reading Tolstoy in a corner. We fell in love and got married a year later in her home-town temple in Kyiv Ukraine, binding ourselves together for time and eternity. We were both virgins until our wedding night. We’ve been married 14 years now and have three children, who are themselves beginning their spiritual journeys with nursery, primary and baptism.

These are many of the beautiful elements of my culture.

Now, what was wrong about it?

In my early 20s, I began to ask harder questions about the claims my church made about itself—questions about the origins of the Book of Mormon, the character of the founder of the church, Joseph Smith, the practice of polygamy, and the likelihood that of all the religions in the world, mine happened to be God’s favored, chosen one. I had been taught to think about religion in dualistic, true/false ways and once I applied enlightenment ways of thinking to my faith, belief as I had known it became unsustainable. That same tendency for fundamentalist, black/white thinking meant that our tradition does not by and large produce complex or beautiful art, nor substantial intellectuals, nor patterns of culture that are deeply attractive to outsiders.

We are a generous, kind, and productive people, but our culture is less good at beauty, mystery, complexity, or tragedy and so anybody in the tradition seeking spiritual growth in the form of contemplation, mysticism or mythic patterning often feels unsatisfied and often leaves their faith and become nones.

I believe that authentic religious life is the only path to resisting the dehumanizing forces of our time. But the question for me is how can we create communities where our children can be deeply formed by love, education, sacrifice and faith but also be supported as they move through each stage of spiritual development towards higher forms of union with themselves, each other, the natural world and God. How can we have high-demand faith but also nurture the path of kenosis and theosis?

This was a public address originally delivered at the 2025 Doomer Optimism Campout at The Wagon Box.

Having walked a similar path since birth I’ve seen a big difference between the church culture in the US and the church culture in other countries. Being Hispanic the way Latter Day Saints mix that with their own cultural heritage brings a lot more of the beauty, complexity and tragedy. They coexist and it’s beautiful. I’m back in the US and I miss that!

“We are a generous, kind, and productive people, but our culture is less good at beauty, mystery, complexity, or tragedy…”

So resonate to me. Thank you, Zachary!